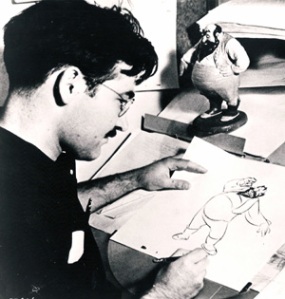

1. Bill Tytla

Disney animation is unlike any other type of animation. There is something about the power and strength of the feelings and emotions of the characters that make this word come to mind. It’s this pure, completely honest emotional connection that makes the Disney films impact people so much. They can make audiences feel these powerful emotions to the point that they feel them themselves and the stories are therefore real in their hearts. For this to be achieved in its strongest form there has to be no difference between the inner and outer emotions of the characters: it’s the feeling that is most important in this type of animation and technical aspects (draftsmanship, timing, spacing, etc.) should only be used to communicate this emotion. Animating is also a spiritual thing. When you animate you’re making a statement, you’re expressing something, and most importantly putting your thoughts and feelings on paper. This form of expression has a lot of heart and soul to it. There’s nothing like it. The connection between animator and character can be strong to a point that most can only fathom understanding. To achieve the maximum result in Disney animation it has to come from someone who really understands this, is willing to work their butt off on it, won’t let anything stop them from achieving this no matter how hard it can be, has inspiration flowing through them, has a strong sense of sincerity and sensitivity, has passion in their artistry, is strong and courageous enough to survive criticism and setbacks, knows exactly what they are doing, and most importantly cares for their characters as if they were real human beings. These qualities are what separates the animators who have made it on this countdown from the rest of the animators. This is what made them able to do animation that is so strong and fulfilling.

The possibilities and potential of animation are endless. It’s a never-ending struggle, a persistent drive, and one that could very well be just an impossible dream. The best stuff that’ll ever be done is hopefully still yet to come and the potential of the medium is going to be more and more fulfilled as the future continuously comes. With all these things in mind it’s essential that if you are going to do this and fully embrace this journey that you sincerely love animation all the way. This is the only way that the impossible dream of Disney animation will ever be achieved. One person who understood this was Bill Tytla, who is indeed in my book the most influential animator in Disney history and the subject of this post.

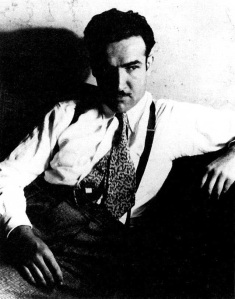

Vladimir or, as he was much preferably called, Bill Tytla is really the ultimate example of what the ideal animator is and the one who really proved the direction that Walt Disney wanted the animation at his studio to go in was possible. He transcended what could be done in Disney animation, did things in a way nobody else has ever done, and he really was the one who showed the world how strong and powerful the feelings and emotions of cartoon characters can be. In many ways Bill was in a sense an enigma. Not only did he have a unique style and approach but he also had an interesting situation: he doesn’t really fit in with the old time animators who were groundbreaking and innovative but unsophisticated and unable to keep up with the direction the studio was going but he doesn’t really fit in with the more refined, polished group that held the roost for many decades.

Tytla really was in a class by himself and was between these two generations. He was older and came to the studio with more experience that the second group (he also had an early departure that’s a whole other story) but unlike the first group he had formal art training, peaked in the feature area and wasn’t a star in the days of the shorts, and had animation that was more sophisticated, deep, and strong than anything ever done at the studio. Another interesting thing about Bill is that unlike many animators who have great acting and emotions but limited draftsmanship or have excellent draftsmanship but less impressive animation and acting he really was the big man on campus in both areas. His stuff has phenomenal drawing, acting, creativity, and feeling. Tytla didn’t have the limitations of an analytical style, the coldness of a technical approach, or limitations in his draftsmanship to stop him from getting the highest possible result.

His animation has no gap between the inner and outer emotions of the characters, making it even greater. The uniqueness of this situation allowed Bill to have a stronger influence on the art of Disney animation than would have been possible in any other case and the power and feeling in his work allowed him to animate at a level that certainly hadn’t been done before and arguably hasn’t been achieved since. “It was mentioned that the possibilities of animation are infinite,” he explained. “It is all that, and yet very simple- but try and do it! There isn’t a thing you can’t do in it as far as composition is concerned. There isn’t a caricaturist in this country who has as much liberty as an animator here of twisting and weaving his lines in and out. But I can’t tell you how to do it- I wish I could. To me it’s just as much of a mystery as every before. Sometimes I get it, sometimes I don’t. I wish I knew, then I’d get it more often. The problem is not a single track one. Animation is not just timing, or just a well-drawn character, it is a sum of all the factors named. No matter what the devil one talks about- whether force or form, or well-drawn characters, timing, or spacing- animation is all these things, not any one. What you as an animator are interested in is conveying a certain feeling you happen to have at that particular time. You do all sorts of things in order to get it. Whether you have to rub out a thousand times is immaterial. The whole thing in animation, as in any of the arts, is the feeling and vitality you get into the work.” “Bill Tytla was the greatest draftsman I’ve ever known- in animation or anywhere else,” praised Zach Schwartz. “He was not a cartoonist; he was a sculptor, and his work had tremendous power and a sense of form.” “Bill was all-out sincerity,” remembered honoree Eric Larson. “He’d act out a scene in his room and I thought the walls would fall in. he was a bundle of nerves, he exploded in his normal life.” “He had an intuitive feel for what a character should do,” simply put honoree Frank Thomas.

“He had such a connection with the thing he was doing it wasn’t really drawing,” explained George Bakes, who was Tytla’s assistant during his days working in commercials back east. “It was Bill that was coming out. He would feel it and struggle until it happened- the tremendous feeling that was him. That’s what sets his animation apart from anybody else’s.” He animated several of the greatest and most fulfilling scenes ever done at the studio. Bill’s best work includes the dwarfs (especially Doc and Grumpy) in Snow White, Stromboli in Pinocchio, Yen Sid and Chernabog in Fantasia, Jose Carioca in Saludos Amigos, and the elephants (Dumbo, Mrs. Jumbo, and the Gossipy elephants) in Dumbo. There’s never been anybody like him and he’s truly at the very top of the art form. Unfortunately Bill’s career was cut short when he mysteriously and abruptly left the studio in 1943 and virtually disappeared from the animation industry. It’s been found out in recent years that this was a decision he regretted the rest of his life and suffered greatly from it.

Vladimir Peter Tytla was born on October 25, 1904 in Yonkers, New York to parents that were immigrants from Europe. Although he was born in America he was unmistakably ethnic and was the first member of his family born in the country. Growing up with very little money and surrounded by lots of religion (which he resented), he found art as his escape as well as his passion and talent. When Bill was young he would copy from the comics in the paper and draw scenes on butcher’s paper. His interest went to the next level when he was in bed for a year due to an illness and passed time by drawing. When Tytla was 10 years old he went with his uncle to see Windsor McCay’s animated short Gertie the Dinosaur at a vaudeville theater and was blown away. “He never forgot it,” remembered his wife Adrienne le Clerc Tytla. “Even years later, he still spoke with the same awe and reverence he must have felt on its original impact. There was no doubt that Gertie the Dinosaur had changed his life forever. “ Going into his teens the young man began to take his talent more seriously and began taking tons of formal art classes. He would spend hours doing them and he was very intense with his studies. It got to the point that after one year of high school Bill dropped out of school. In fact his inadequate attendance sent him to a trail for truancy but the judge was so impressed by his work that he let him go. This allowed him to get even more serious with his formal art training and he took classes at the New York Evening School of Industrial Design.

At age 16 Tytla began working lettering title cards at the Paramount Animation Studio, where he met his future Disney colleague Ben Sharpesteen. Although in his late teens and early 20s he was uninspired by animation (it was very primitive at this time and there really wasn’t a lot to it) and didn’t have any desire to pursue a career in it his family needed the income and he learned his craft at John Terry’s studio in 1922. The following March he got his first job as an artist in animation when he was hired by John’s brother Paul Terry, who was starting up his Aesop Fable’s series. It was here that he first met future colleagues such as Norman Ferguson, Ted Sears, and Hicks Lokey. During his time on the Aesop Fable’s Tytla proved that he could do unbelievable amounts of quality footage at a very fast rate. This made him become one of the highest paid animators at the studio extremely fast. “Years later Paul Terry told me he would have given Bill even more money if he had asked for it,” remembered animation pioneer I. Klein. “Bill Tytla was a brilliant animator from the very start of his career.” However it was being an artist that was Bill’s prominent gumption and on the side he lived the young artist’s life taking tons of classes and working endlessly to make his work the best it could be. He wanted to work with the masters of fine art and work for them, eventually becoming one of them. At this time animation was fading and the brief period of success for cartoons had ended.

The traces of promise and artistry in Windsor McCay’s shorts weren’t at Terry’s and the quality of the cartoons was very low. During his five years working on the series Tytla didn’t change his attitude or interest towards animation so therefore in 1928 he left for Europe to make his dream of learning from the masters there a reality. During his eighteen-month stay he did extensive studies in sculpture, painting, and all forms of art as well as took in tons of inspiration. One of his best experiences there was learning from Boardman Robinson, a great artist and illustrator. “I heard he was really a tough guy,” reflected Bill. “He looked like a man and talked like one, and he had a very fine subtle sense of humor. He glared through one drawing after the other, kind of casually, and turned to me and said ‘They’re kind of clever, aren’t they?’ then he got to work on me. He insisted I drew with a sharp-pointed pencil so I would have to draw and no technique. He also recognized I tended to draw on the flashy side and thought this would help.” Another great inspiration for the young man at this time was Pieter Bruegel, a Renaissance artist who was his favorite artist of all time. He constantly went to study his paintings at a museum in Vienna, Austria. “It was my epiphany,” he told John Culhane. “I stayed in Viena and went back and back. I knew this was what I wanted to do but I wanted to make them move.” If you pay attention you’ll notice that in Tytla’s animation you can see aspects that show inspiration from Bruegel- drawings that tell a story, boldness, dynamic expression, simplicity, etc. Another great piece of inspiration that he acquired from his time in Europe was his studies in sculpture. This would have a profound influence on his animation and his drawings from that point on were always very sculptural: they’re forces instead of forms and are really 3-dimensional in terms of feel.

As inspiring as his stay in Europe was Bill began to realize he could never reach the artistic level of the masters and decided to return to America. When he returned he was immediately offered a job by Paul Terry at his studio Terrytoons which he expected in part because of the Great Depression and his desire to make his art move. While Tytla was an above average animator before he went to Europe he was at a whole new level when he came back. All of his stuff during that period shows great three dimensional and solid drawing as well as powerful forces in the movements. Bill was also significantly better at anything related to personality animation than anyone else at the studio making him always get cast when it was needed the most. “If it was a difficult or personality thing you’d give it to a fellow like Tytla,” stated Paul Terry. Actually by this point an animator like him was a very odd fit for a studio like Terrytoons. Terrytoons made very low quality cartoons and it was very hard for any animator to improve there. It was a very weird situation that an animator so inspired, brilliant, driven, and hard working would be at such a primitive and flaccid studio. “They were making tremendous amounts of money but we had to hire our own model ourselves and of course they wouldn’t even consider an instructor,” reflected Tytla. “The lead animators couldn’t do much if you took them off cats and mice. They couldn’t animate girls, we would have to. Or if there was a dance sequence you might go to dancing school and ask for a couple of routines. It was pure accidental that one or two of us liked drawing and went to art school. Finally we had to give up our models. The fellows would make wisecracks at the girls who posed for us. They’d say ‘What the hell do you go to art school for? You’re animating, aren’t you?’”

However when back at Terrytoons the animator met and fastly became best friends with animator Art Babbitt, who would later change his life. In 1932 Art moved out west to work at the Disney Studio and was hugely impressed by it. For over two years he insisted that Bill follow him to the studio and told him that he would never want to come back. However the other man was a bit reluctant to go on the bandwagon because he had a job in the Depression and was providing for his family. However in 1934 Bill could resist the temptation no longer and went out to California to take a look at the studio. “Jesus, I was impressed by the Disney Studio,” he recalled years later. On November 15, 1934 Bill Tytla was hired by the Disney Studio as a full-fledged animator and the rest is history.

For roughly his first year at the Disney Studio Bill Tytla spent his time animating on a couple of shorts. Even during this probationary year he showed his mastery and skill when using weight, anatomy, timing, and force in animation. Among his early assignments were Clarabelle Cow in Mickey’s Fire Brigade (this shows his ability in terms of acting and expression but for such a simple character his use of anatomy can be a bit overwhelming) and the Angel and Devil Foodcakes in the Silly Symphony Cookie Carnival (this shows his skill when it came to force, perspective, and depth in mass.) However the most significant of these early successes was on a short called the Cock O’the Walk, a Silly Symphony involving dancing roosters. To sum it up his animation on the short is simply brilliant. All the genius details (the weight, fluidity in movement, chorography, timing, acting, character walks, personality, and expertise in performance and movement) work very cohesively and effectively to communicate that this rooster is a big bully. I highly recommend freeze-framing the dance sequence to really understand how this all works together. Not only is the quality and depth of drawing in the animation spectacular but there also is something in that sequence that was completely new: power.

No animation had ever had such power to it and it’s one of the first pieces of animation done at Disney that suggested the potential strength that could come in an animated performance. This is not only strength in action and force but also strength in emotion and feeling. It’s hard to define because those two things are so interconnected in all of Tytla’s animation. This really is a big part of what sets him apart from other animators: these things are interchangeable and together they work significantly more effectively than they would if there was a distance between them. In many ways Bill’s animation in this short feels even more real than something realistic because of the real feeling depicted in the movement and the acting. It’s not realistic but it’s believable. “The first duty of the cartoon is not to picture or duplicate real action or things as they actually happen, but to give a caricature of life and action,” Tytla explained. “The point is that you are not merely swishing a pencil about but you have weight in your forms and do whatever you possibly con with their weight to convey sensation. It is a struggle for me and I am conscious of it all the time. You must phrase or force or define animated drawings so that the eye always follows. Very often you must do things you might call bad drawing in order to accent or force. On the screen it looks good but that one drawing in itself doesn’t mean anything. It’s just a continuation of a vast whole. You must force or accent certain drawings in order to get a certain mood or reaction across. If you always try to keep perfect form you will not get the feeling across. It will be without flavor. You can force or accent a hand and throw it way out and bring it back down. You can twist an eyebrow or a mouth, you can do something to the little character’s shoulder and cheat but it is a continuous flow and it always comes back to its original shape.”

His animation in the Cock O’the Walk got huge acclaim across the studio and it was where he really proved himself to everyone, including the boss. “Your animation in the short was a big step forward,” wrote Walt Disney with great praise. “Something was started which is what we are striving for. That is doing things which humans are unable to do.” At the same time Bill was really beginning to embrace the opportunities given at the Disney Studio and came to really appreciate them as well as really feel the sense of excitement and desire to improve that was contagious at the studio. Among the privileges he cherished were Don Graham’s action analysis classes and the sweatbox sessions. “I fell for them like a ton of bricks,” said Tytla on the action analysis classes. “It was really a life saver for me. I was in the period between the old and new stage of animation. Running films in slow motions was like lifting a curtain for me. The sweatbox sessions were another revelation. After all if you run your piece of animation over enough times you must see what is wrong with it. Formerly I never saw what I animated. We would catch a movie ever two weeks to see a scene we had experimented on for drawing or spacing or timing but we couldn’t get much benefit from one viewing. In the theatre they would only run the picture twice- the whole thing whizzed by and you forgot all about what you had tried to do. And unless you did go to the movie, you would never see what you had done. Furthermore, I never saw a thing run in reverse except once in New York when they ran a scene backwards of a fellow diving off a board. My boss in New York never knew about a moviola- he probably still doesn’t. When he got a letter from one of the boys here telling him about the tests-roughs, semi-roughs, semi-cleanups, cleanups, and finals- then the whole thing is done over again, he wouldn’t believe it. My boss thought it was funny as hell- a bunch of guys running around in hallways with pieces of black and white film in their hands looking at moviolas. He said ‘When I hire to a man to animate, I want him to know how.’ The things done here now, I would consider sensational and I know the fellows back east consider them sensational when they hear descriptions of the training and opportunities here. But here at the studio those things are considered commonplace. The average fellow her doesn’t even realize what is shoved on him. He is being coaxed and encouraged to do better work, and he probably thinks it is a pain in the neck. I really can’t compliment Walt and the organization enough for handing out the stuff. There is no other fellow who will do it. These things, plus all the art school training, influenced my approach to the work.”

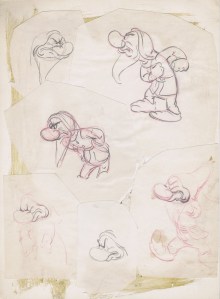

In December 1935 Bill Tytla was one of the first animators assigned to Snow White, Disney’s first feature film, and along with Fred Moore was one of the lead animators on the seven dwarfs. There are a lot of notable differences between the animation of the two men in the film. While Fred’s animation is more appealing and charming it is Bill’s where the distinctiveness of the dwarf’s personalities and their emotions come out. While the dwarves are relatively interchangeable when it comes to acting and movement in Moore’s work Tytla’s work makes all of the men have strong personalities (e.g.- he clearly defines Doc as the leader and Grumpy as the cynical voice of reason through their acting and movements while in the former man’s work all the dwarfs are very jolly and pretty similar), specific character relationships, individual walks and movements, and best of all strong feelings. “I’ve never had a problem like that come up before because here were have a group of characters that are rather alike yet all different,” he commented. No other man could solve the problem in such an impacting way. While Fred’s sensibilities were prominent in most of the dwarfs it was Doc and especially Grumpy that worked best with Tytla. A great scene to study is the part in the Spooks sequence where the two of them are conversing. Bill tells you all you need to know about the characters just through his animation (even the lip sync is incredibly specific to the characters) and for the first time we really see the great understanding he had for emotional material. In that scene as in all of his animation in the film there is exceptional cartoon acting, which is the use of caricature and the principles of animation to communicate who a character is and what they are thinking.

Indeed Tytla’s acting in his dwarf animation is was the most complex and specific that had ever been done at the studio. One interesting example of this is the way he used expressive distortion to show the combination of the physical and emotional feeling of an action. “I got a huge kick out of the way Tytla would distort something,” commented his then-assistant Bill Shull. “Stretch it out as that it looks almost silly. When you see it on the drawing you would swear it would mean nothing but on the screen these things seem to hold the scene together.” You don’t see the distortion on the screen (part of the reason it works in his animation is it’s still very solid and retains weight) but you really do feel it and in turn you feel inside what the dwarfs are feeling. While there are way too many things that can be discussed and studied related to Bill’s animation of the dwarfs in a nutshell he has two real standout scenes in the film. The first is the song sequence where the dwarfs go out to wash. An interesting thing about the scene is that the timing with the music reflects how the dwarfs are similar but the movements and actions he applied show their differences. Not only the timing is great but also the essence of the personalities and the emotional complexity of the characters, particularly Grumpy. In this scene he animated forces before forms, meaning that instead of being focused on the graphic qualities of the character he focused solely on the feeling brought by the acting and action. In that section a must freeze-frame is the scene of Grumpy mocking the others while sitting on the barrel. His expressions are incredibly clear and the specifies of the performance is a great merit.

The second one is the scene where Grumpy tries to resist a kiss from Snow White but after walking away he realizes he really is in love with her and has deep feelings for her. This communicates the emotion to the audience so powerfully and we finally realize what his emotional situation is. Grumpy’s embarrassed about his feelings for Snow White and feels like he’s too smart to show such a soft spot so he tries to cover it up by resisting her but at this point he no longer can control it and it is revealed that he probably has the deepest feelings for her of the seven. This whole situation completely came out of Tytla’s mind and it was him that put in this element, which really makes the story that much deeper. In conclusion his work on Snow White really showed the potential for how powerful and strong the feelings of the Disney characters could be as well as how high the level of acting could reach in an animated cartoon. “Bill’s approach to animation is a confirmation of all that the instructors have been trying to do here for four years in drawing classes,” analyzed Don Graham. “It is the first time that these principles have been evident in animation and the first one to think in terms of forces instead of forms. Tytla’s work has been a revelation.”

Around the same time Bill married Adrienne le Clerc, who was a model for the drawing classes at the studio. Around this time he said these very inspirational words of wisdom at an action analysis class: “You fellows possibly may think that just because you are doing a bunch of Ducks and Mickey’s that all you must do is learn how to draw well enough to draw a Duck or a Mickey. But the funny thing is that the more you know about drawing the more ably you will handle the Duck and the other character. And besides five years from now you won’t be doing ducks anyway. The type of stuff we have been doing the last few years has been a change from what preceded it and will be different from what is about to follow. You men who have animated before will agree that there has been quite a bit of change since you started animating. Today we are not merely trying something- we are really on the verge of something that is new. It will take a lot of real drawing- not clever, slick, superficial, fine-looking stuff but really solid, fine drawing- to achieve those results and those results will have to be achieved by fellows who have absolute control over what they are trying to do. These animators will have to be able not only draw but to take a figure and no matter how they twist, distort, slap, or extended that figure it will still have weight. These animators will have to be able to put across a certain sensation or emotion- for that is all we are trying to do in animation.”

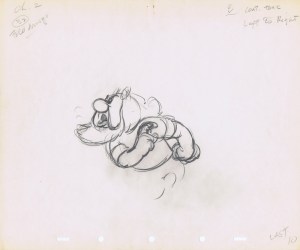

Having emerged to stardom with Snow White Bill Tytla continued to receive tons of quality assignments at the studio and became one of the most productive animators there. His first animation after Snow White was on the short the Brave Little Tailor where he animated the cartoony but heavy giant. This unfortunately for him began a string of typecasting towards heavy characters, something that he didn’t particularly enjoy or that really showed his full potential as an animator. Up next came the Sorcerer’s Apprentice (which eventually would become part of Fantasia but at this point was just a short) where he animated all of Yes Sid the sorcerer. He is a very reserved, intelligent, and wise character, which is clearly communicated through Tytla’s animation of him. An interesting thing about it is that the poses he used are so loose and expressive but the construction is really sculptural, detailed, and has great volume. However Bill’s signature work from this period is Stromboli in Pinocchio (he also animated some of Geppetto in his earlier scenes including a very meaningful scene where he realizes Pinocchio is alive.) Stromboli is one of the scariest and heaviest Disney villains and certainly is the most explosive. Many animators recalled in interviews that when animating the character he would act it out himself by jumping and summing around his room. The biggest criticism that can be given to Tytla’s performance on Stromboli is that there is too much movement and it’s overacting. Sometimes his animation can be a bit too much for the material and the acting is a bit overdone in terms of how much action is going on. However the acting is still top-notch if you can look past the overuse of it. Even studying Stromboli’s lip sync alone is incredibly interesting and from that little detail you can see the brilliance at work. You really feel the threat, vigor, desperation, and cruelty of the character through the way he acts and moves. I highly recommend freeze framing Bill’s scenes of Stromboli because you’ll see in full blast excellent acting, staging, timing, spacing, weight, poses, feeling, bold movement, and powerful animation all at the same time (it’s rare to see all these aspects working together so well and even better paired with fantastic draftsmanship.) However it was a character that Tytla struggled getting started on. “I gave it everything I had,” he recalled. “All of them said ‘Great’ or ‘Nothing else is needed.’ Finally, the time came for Walt to see it. He was subdued and said ‘That was a helluva scene, but if anyone else had animated I would have passed it. But I expected something different from Bill!’ well sunk a ship with that remark. It took me a couple of weeks before I could work again. I was crushed. But one day I took up my pencil and started to draw again differently. It was as if something hit me and I started all over again. This time Walt said ‘Great! Just what I was expecting!’ He never explained what was wrong. It was as if by some magic way you would know.”

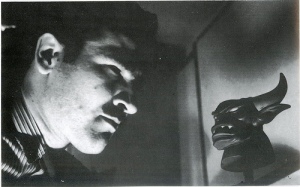

After Stromboli Bill Tytla did his last heavy for some time and a very interesting one: the evil, powerful Chernabog the devil in the Night on Bald Mountain sequence in Fantasia. It’s arguably the most powerful and intense scene to ever be animated. “Never again has there been anything as powerful as Tytla’s devil,” stated the candid, hard to please Milt Kahl. “Bill had a pretty definite idea of just what he wanted to animate before we ever got to the live action stage,” reflected Wilfred Jackson. “The actor assumed he was there to give his own concept of the character. Bill came flat out and said ‘I don’t like it. I like it better when we went through it and I’m going to animate it that way. It would help if you would go in front of the camera and go through it that way for me.’ So I took off my shirt and we shot film of me as the devil.” “I’d look into this dark bottomless pit that snuffling and grumbling were coming out off,” remembered his assistant Robert De Grasse. “He would work for hours and never take a break. I doubt he even knew what time it was.” It is also indeed the flashiest thing that has ever come up on the Disney screen and there is absolutely nothing like it. Personally my favorite thing about Bill’s devil is the intensity of it: it really resonates in his animation and you really do feel tension when it’s on screen. He’s absolute pure evil in every way. From a technical standpoint it’s flawless: the draftsmanship is breath taking (personally I can’t believe how well drawn his hands are), the weight has a huge impact, the anatomy is completely accurate, and the movement is perfect. From an acting standpoint Tytla took it to the next level. “I imagined I was as big as a mountain and made of rock yet I was still feeling and moving,” he commented. It’s incredibly advanced and it really does feel like a huge devil made out of rock when he moves. The most powerful point of course is when the church bells ring and he posts his arms out to defend himself. It has so much dynamic power to it and really shows you this is one incredible animator doing this.

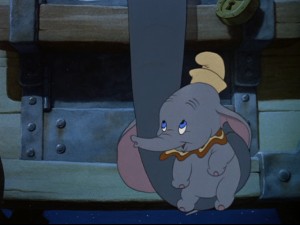

However it was the next film that really was Bill Tytla’s best work. The film was Dumbo and he was assigned to be the lead animator on all the elephants including the Gossipy elephants and the very emotional relationship of Dumbo and Mrs. Jumbo. To sum it up this could very well be argued to be the greatest animation ever done anywhere in the art form’s history. The character relationship of Dumbo and Mrs. Jumbo is without a doubt the most emotional, strong, and powerful one ever to come out of the studio. “I would hand out scenes to Bill but there would be others who worked with him who would do certain scenes,” explained Wilfred Jackson, who directed most of his scenes in the film. “Quite often he would knock out a few poses to get them started and would supervise what they did very carefully.” Even though they never speak to each other during the film (Mrs. Jumbo only has one line and Dumbo is completely mute) there is such a strong sense of sincere, endless love between the two characters and it really impacts the audience. For the inspiration Bill looked towards his experiences as a parent and his feelings for his two-year-old son Peter to find the emotional side of the characters and communicate it through his animation. “I don’t know a damned thing about elephants,” he explained. “I was thinking in terms of humans and I saw a chance to do a character without using any cheap theatrics. Most of the expressions and mannerisms I got from my own kid. There’s nothing theatrical about a two-year-old kid. They’re real and sincere- like when they damn near wet their pants from excitement when you come home at night. I tried to put all these things in Dumbo.” Indeed he was successful in putting them in. Tytla was able to use physical contact between the two to really make his animation warm and sincere. There is something in this animation however that can’t really be analyzed or explained technically- something that is just too strong, specific, and sincere of an emotion to understand or articulate. It’s the thing that makes the jump from trying to become a character and thinking about what they feel like to actually having the real feelings the character is feeling. It’s something so elusive and that’s what makes it so unique- it’s completely honest and real. This is why Tytla’s animation in this film is so personal. He really made a statement about human emotions, the meaning of the relationship between parent and child, what it means to truly love someone, and most importantly about himself. No other animator has come anywhere close to achieving this EVER. It transcends method acting, formula, analysis, and anything else- it’s just purely emotionally real. It’s pretty ironic that decades later it was actually discovered that elephants have similar emotions and relationships- here it was so strongly in 1941.

Bill’s animation of the gossipy elephants is also a big accomplishment as well. You can tell that he must have been observing a lot of gossipy women for inspiration because it really is so real and familiar. Not only do I love the acting and performance Tytla used on them but also the 3-dimensional sculptural drawing he did of their faces and best of all the brilliant timing. A great scene to study is the one where the matriarch is talking about how elephants are always supposed to have dignity. Not only does the timing really communicate the point of the scene and is right to every rhythmic beat but the performance is spectacular and incredibly specific to the character. You can read clearly how this character is and their personality. The expression in the scene is also phenomenal. However there are two scenes Bill did in Dumbo that truly stand out. They show that he really took serious Richard Boleslavsky’s advice to heart: “If you are a sensitive and normal human being all life is open and familiar to you.” The first is the bathing scene, which is truly a beautiful piece of animation. It really shows us how deeply emotional Mrs. Jumbo and Dumbo’s relationship is and how close they are. This really makes the picture work and makes us feel for the characters. The second scene that truly is phenomenal is the one where Dumbo comes to visit his mother in prison and he swings in her trunk during the Baby of Mine Song. This is without question the most emotional scene ever animated at Disney and personally the one that speaks to me more than anything else done at the studio. You could spend days analyzing the greatness of the scene but there is one shot that really shows how great of an animator Bill Tytla is. While anyone else would go straight for the tears when Dumbo sees Mrs. Jumbo’s trunk and think through the acting analytical, what he did is he shows the elation first and then goes into the tears. That one change makes all the difference: it’s so much more powerful and real. There’s absolutely nothing analytical or insincere about that shot. It’s pure emotion and a strong one. “He was telling the audience exactly what he wanted to tell them,” explained Frank Thomas. “He wasn’t showing how smart he was or how much he knew but was doing what was right for the picture. His animation just overwhelms me.”

As sad as it was the good days couldn’t last much longer. Bill Tytla found himself in a very awkward situation where he had to choose between his best friend Art Babbitt and staying loyal to the studio he loved when Walt Disney fired the animator for labor activity and lead a strike against the studio. Under pressure and extremely torn Bill chose his friend and on May 28, 1941 was out on the picket line. The extent of his involvement in the Strike and the vigor he had towards out has been a subject of much debate for decades. While some try to say that Tytla didn’t want to do anything against the studio and even though he technically went on strike really was just at home miserable for it, others say they were surprised at how vicious he was even about the subject of Walt and cursed at them. Emery Hawkins remembered it as he really wasn’t there much at all and hide at home upset he ever went out while Joe Grant remembered him suggesting he should replace Walt as head of the studio. Personally I don’t think we’ll ever really know exactly what his motivation and situation was regarding the strike. While I don’t completely believe he wasn’t vicious at all during it I do believe that he didn’t want to do anything against the studio. He had this to comment on the subject: “I was for the company union, and I went on strike because my friends were on strike. I was sympathetic towards their views but I never wanted to do anything against Walt. I tried to work out a solution with him but somebody told him not to work with me.” While it has been written that Tytla left the studio directly because of the strike and was gone right after it happened, that’s not really the reality of the situation. When it ended in fall 1941 he was immediately back at the studio and actually did quite a lot of good work after the strike. The greatest of these would probably have to be his animation of Donald Duck and Jose Carioca in Saludos Amigos, which has beautiful choreography. “Bill worked me over as I directed him,” remembered Wilfred Jackson. “When the parrot was to pat the duck’s head he would pat my head to see what it was like.” However while Jackson’s description sounds pretty consistent with the Old Tytla some others remember him being a changed man after the strike. “He was aloof,” reflected animator Bob Carlson. “He just stayed by himself. He didn’t mingle with the guys very much anymore. He just came to work, stayed in his room, and went home.” Others recalled that he constantly yearned his farm back east. On top of this Adrienne wanted to move to the Connecticut farm and the work during the war was pretty unsatisfying for an artist like Tytla. Among his final work for Disney is a witch and Nazi teacher in the brutal short Education for Death and a fight between an octopus and eagle in the feature Victory Through Airpower. His last credit was on the short Victory Vehicles. In January 1943 Paul Terry went out to Los Angeles and gave an offer to Bill that he accepted. On February 25, 1943 he resigned from the Disney studio and abruptly disappeared from the Hollywood animation industry. We’ll never know exactly what made this happen but we do know that it was a depressing loss for the studio and one Tytla would regret for the rest of his life.

At the Terrytoons studio Bill Tytla quickly became very unsatisfied and really missed the Disney studio. The quality of the cartoons wasn’t much better than it was during his previous time there and he really struggled adjusting to it although he actually did do some good animation at the studio and even a few places show faint traces of his greatness (something that’s very hard to do in a Terrytoon.) “I think it was frustrating for him,” explained John Gentiella. “He really couldn’t do what he wanted to do. He was such a perfectionist.” Ironically to save finances Bill was let go from the studio in the summer of 1944. He soon found work as a director at Famous Studios, which turned out to be not much better. While his cartoons have better staging than the rest of the studio’s work they are for the most part interchangeable from the work of the other directors and he wasn’t a very good director. Around this time he tried to convince the Disney Studio to send him work to his farm to animate but that was unsuccessful although he would try to come back to the studio many times later. After leaving Famous in 1950 he paired up with former Disney colleague at Tempo Studio in New York, where he struggled with the modern style of the work. After this he worked in commercials in the east and struggled greatly. He missed the style and fulfillment of Disney animation greatly. As much as he wanted to come back the committee at Disney didn’t want the competition and prevented this from happening although people suggest that Walt would have accepted him back. While it pains me deeply to talk too much about the sadness and depression of Tytla’s later life to the point I’m writing about it as briefly and delicately as possible I will tell you it wasn’t a happy ending for him and it was a true tragedy (read John Canemaker’s monograph on him to learn more about this. Thanks Rhett Wickham for letting me borrow a copy.) The worst thing is the loss was mutual. Bill was precisely the piece that the studio needed during the late 40s, 50s, and 60s. The power and feeling he wanted was the only thing needed to make those films even better than the classics they are. You can only imagine the greatness that could have been achieved. On December 29, 1968 Bill Tytla died on his farm in Connecticut after a severe long-term professional, physical, and emotional decline. However as terrible of an ending as this may sound there is some happiness to be seen. No matter what Tytla’s influence will live on at the Disney studio forever and his greatness will never die at the heart of it.

Bill Tytla’s style is very unique and dynamic. His stuff could range from realistic bold anatomy to caricatured expressive distortion. Acting wise he could go from an evil devil to a baby elephant so there really was nothing the man couldn’t animate and animate well. The most important thing to understand however in his style is that feelings and emotions always came first for him. Bill did everything possible to get this out of him and really struggled with it until it all came together emotionally. These feelings can range from very bold to incredibly subtle but they always had a great dynamic power to them. A huge influence on his acting was the book Acting: the Six Simple Steps by Richard Boleslavsky. Tytla intensely studied this book and really took the advice from it to heart. It talks a lot about method acting and if the term is possible he was in many ways a ‘method animator.’ Bill really cared for his characters and did everything possible to get as much inside them as possible. He tried to become the character and always felt real emotions towards them, therefore making his animation very strong and incredibly personal. Draftsmanship wise Tytla’s work can be a bit on the flashy side and has great strength. It’s got a very sculptural feel and is very versatile. Another important thing to realize about his animation is that he really tried to animate forces in actions and movements. Instead of being focused on the form he was most concerned with the feeling obtained by going through that movement and action. Not only does this involve the feeling of the action but also the feeling inside the character emotionally. These two are very connected in Bill’s animation and therefore have a much stronger result than they could if they were more distant. Last is Tytla’s animation was very sincere and has great integrity to it.

Obviously the influence that Bill Tytla has had on the art of Disney animation is incredibly overlooked and truly is immense to no end. Like I’ve tried to say throughout this entire post he really d transcended what was thought to be possible in animation. There’s nobody like him and his uniqueness is part of what makes him so influential. For one thing Tytla was one of the first animators to really take acting seriously. He really got inside his characters and did everything he could to make them have an impact on an audience. This really changed the way animators thought of acting and this inspired them to try to do the same thing in their own animation. Also the intensity and strength of his work really influenced everyone at the studio to really try to find very personal, strong, and powerful work that was completely their own and really spoke to people. Bill’s work really makes a statement and is artistic expression to the highest level. Another thing is that he was the one who proved that it’s important to really animate forces in animation and that it’s even more important than focusing on the forms. This really made Tytla’s work unique and strong. It’s also important that he proved that animation is at its best when there is no gap between the inner and outer emotions of the characters. Disney animation is supposed to be sincere and this is really the way you do it. You have to really make that inner emotion resonate in the animation and come out for the audience to feel it. Last is Bill Tytla really inspired the animators at the Disney studio to really take their work to the highest possible level and really get inside their characters emotionally. No one else did work so personal and honest. The other animators really picked up on this and tried to emulate it. As a result the feelings and emotions of the characters has been the top priority for Disney animators ever since and everything else is just there to support them. If it weren’t for Tytla no one could ever know the potential that was there and realize how strong they could be. Of course there are many more ways that Vladimir is influential but these are just a few that come off the top of my head.

Personally, Bill Tytla has had a strong impact on me. His work changed the direction of my life and was what really made me feel passionate for animation. I still drop my mouth at how powerful, emotional, beautiful, personal, and strong his work can be. It’s true merit and exactly what I value most in an animator. I remember freeze framing through the bathing scene in Dumbo and feeling in my heart ‘Wow something this honest and emotional is possible. A man could put this down on paper? I really have to try to do this.’ It really struck me in the heart and ever since then I’ve had no doubt that animation is my sincere passion. First Bill’s work really has influenced me to think about animation as a form of artistry and expression. If anyone was ever an artist as an animator it was definitely Tytla. He expressed himself through art in a way that few people ever have. Everything Bill animated at the studio was incredibly personal and done to the highest quality. This really shows and makes his work some of the strongest stuff ever done in animation. Second is Tytla’s influence really made me decide to take my studies and art seriously. He was such a hard worker and it was his determination, persistence, need to improve, desire to learn, and most importantly strive to understand that allowed him to do what he did. You have to have this gumption, drive, and passion if you’re going to pursue a career in a field as rugged and intense as animation. I’ve learned from this that it’s important that you always keep learning, continue to progress and break levels, and of course always do all you can to get the best possible result. You can’t just focus on the details; you’ve got to use them wisely to achieve one cohesive big picture that really speaks to people.

Bill’s animation talks about what it means to express your feelings and make a statement through the art of Disney animation. I also am really inspired by the almost-spiritual approach Tytla had to animation I described at the beginning of the post. It’s incredible to be able to find something so fulfilling and emotionally involved. I’ve learned that the farther you go in animation the more it helps you understand the world, people, human emotions and relationships, feelings, situations, and especially yourself. I’m only at the very beginning of this but I’ve already found my studies and work on my artwork has really helped me understand so much and see the world in a totally different perspective that’s much more philosophical and spiritual. I can’t wait to see how far this understanding can go and where it’ll end up when I’ve actually gone farther on my journey. This really speaks to me in all of Bill’s work more so than it does in anybody else’s. Another important way that he’s influenced me is in understanding the importance of the emotions and feelings of the characters. This is what you’re out there to capture and perceive. This is what this is all about. Without them animation is nothing special much less magical and believable. Particularly in his work in Snow White and Dumbo Tytla demonstrated how far this can take you and the power they can have on people. It’s unbelievable how much a drawing can impact a person emotionally. Last is I feel that Bill Tytla’s work has made me understand the importance of integrity in one’s work and what it means to love something all the way. This should always be your motivation to doing any endeavor or making any decision. You’ve got to be honest if you’re going to be an artist and have to know exactly what you’re doing. If you don’t believe in your work then why would anyone else care about it? The possibilities of animation are endless and it’s impossible to know how strong it can be. What’s important is that you really do all you can and keep that drive. You’ve got to not be focused on the destination and really embrace the journey. Loving something all the way is something that’s very hard to describe and something that’s very hard to understand. It has such strong meaning and it is really prevalent in all of Tytla’s best animation. He loved Disney animation all the way and loved his characters all the way. When it comes down to it it’s really the final test. If you don’t love animation all the way then there’s no reason to bother warrioring through it. This fulfillment is what makes it all worthwhile and ultimately what allows you to be able to transcend the medium, do really meaningful heartfelt work, and best of all really put your own feelings and emotions into your animation. I want to be able to do this someday and hope to really be able to understand it. I feel that loving something all the way is a really important thing to do in life. I feel it’s important with your passions, relationships, and with yourself. There’s nothing more sacred than this and to feel this way you’ve really got to be open minded and understanding. This is probably the greatest thing I’ve learned from animation. I’m really so grateful for everything I’ve learned from this experience of the blog and feel like a better person coming out of it, which is a very wonderful feeling to feel. Thank you Bill Tytla for your contributions to the art of Disney animation and for the inspiration you’ve been to me and so many other people!

And here we go with my first ever posting of a piece of my original artwork….

December 18, 2011 at 2:23 am

Thanks Grayson for your blog and all the research you put into it. It was great to hear your inspiration for animation in Bill Tytla’s work. I had the same feeling when I saw “Secret Of Nimh” for the first time in theaters. I wish you the best in following your dreams.

December 18, 2011 at 12:14 pm

It could only have been Tytla at the #1 position.

December 18, 2011 at 10:35 pm

Great job, Grayson! I know how much work you put into this blog and it shows your passion for the art of traditional animation and it’s history.

I wish you success in your career in the animation industry.

Best.

May 23, 2012 at 8:19 pm

I was watching DUMBO with my two year old daughter this morning and as many times as I’ve seen it, it never fails to affect me. Now that I have little kids, it’s even more intense, especially the bond between Dumbo and his poor mother. I knew Bill Tytla did the animation but I wanted to look up if anyone on line had commented on his wonderful work and I found this blog. Thank you so much. You’ve said what I’ve felt for years about Tytla. Much appreciated!

October 25, 2012 at 5:44 pm

This is the exact same reason I landed here. My daughter (3) just watched DUMBO for the first time this past weekend, and I was struck by the strength and sincerity in the lead’s animation, especially the “Baby Mine”/jail sequence. It’s a shame that, due to how he left the studio, his position as an innovator with Disney and in the industry is hardly known. Where’s a scrappy historian who can put together a fuller account of pre-Nine Old Men Disney and place Tytla in the proper place of respect he deserves?

June 2, 2012 at 2:28 am

If he missed the Disney studio, why didn’t he go back? Couldn’t they have let him come back? Incidentally, he resigned on the same day George Harrison was born!

July 21, 2014 at 10:46 am

Tytla tried to go back years later, but the studio wouldn’t take him back…said they didn’t have any work for him.

July 1, 2012 at 11:08 pm

Hey Grayson, love your list and the time you spent on it. I believe you have all of the correct animators on it but not necessarily in the right order. 🙂 Naturally we all have our favorites…

July 3, 2012 at 4:13 pm

Who are your personal favorites? I definitely made some mistakes i feel in the order(Marc Davis, Eric Goldberg, and James Baxter were way too low)

November 20, 2013 at 1:50 pm

Hey, I can’t thank you enough for putting this list together. I’m just starting out in animation myself and have set myself a whole list of research topics. This is such a good foundation for learning about Walt Disney Studios and the key players behind it. I’m learning 10 animators a day – their names and background. I’ve now got to 40. It would have taken me months getting all the information without your help. 🙂

March 25, 2014 at 12:08 pm

This is an amazing blog! Thanks for all the work you put into this. More people should know about the artists who actually craft these iconic images: the largely unappreciated, talented, dedicated and so very inspirational masters of an insanely complicated medium that we all take for granted. I learned a lot here. Hope to see more like this!

March 25, 2014 at 12:11 pm

Out of curiosity, why no Tim Burton? There are also a few newer animators like Lou Romano and Brittney Lee whose careers at Disney and/or PIXAR are looking promising… Just a suggestion! Or maybe a seed for further posts? 😀

April 10, 2014 at 6:58 pm

Hey Grayson! 🙂

I really enjoyed reading your blog! My favourite animator is Bill Tytla, too!!! His

I’m from Germany und very interested in the art of animation, although there’s a very big distance to the amazing House of Mouse over there …but who knows! Andreas Deja was living here in Germany also for years before he came to CalArts…. 😉

I’ve read you were “only” 16 when you were writing the exciting hit list!! That would mean we’re the same generation!!

Greetings from Europe,

Jannik