14. Wolfgang Reitherman

Many people firmly believe that subtlety and strong key poses are essential to great animation. They look to find strong emotions in their characters and show these feelings through small, subtle gestures and expressions. However some other animators feel that animation is intended to be more creative and imaginative and that you need to utilize the emotions strongly through broad action, dramatic staging, hard work, and maybe even tipping the boat over again. They still believe the feelings of the characters are important but that it they can be utilized and expressed in a completely different way. This second approach is the perfect way to describe the art of Wolfgang “Woolie” Reitherman, number 14 on our countdown and the subject of today’s post.

Wolfgang Reitherman was the man of anything broad action, from comic, entertaining scenes such as Goofy’s hilarious dance in the El Gaucho Goofy sequence in Saludos Amigos to dramatic, intense actions sequences such as the unforgettable fight between a stegosaurus and a tyrannosaurus rex in the Rite of Spring segment of Fantasia. “My work has a vitality and an ‘I don’t give a damn- try it’ quality,” said Woolie of his animation. Reitherman animated straight ahead unlike most of the other honorees but his knowledge of staging (his scenes show an understanding of film and cinematography that most other animators didn’t even today) suspense, and entertainment as well as constant reworking on his scenes made it reflect the assets rather than fatal flaws of that approach. He too was also a very hard worker and stopped at nothing to get every possible ounce of entertainment into a scene. “You know how Woolie is, he’s going to lick this if it’s the last thing he ever does in his life,” said assistant animator and later head of the animation department Ken Peterson on Reitherman’s work ethic. “Woolie compare himself to others which made him work harder,” said the great Ward Kimball on his contemporary. “He was tenacious and didn’t have the quick, facile way of working of Fred Moore or the flamboyant, spontaneous timing of Norman Ferguson. He had to work harder, but he ended up with good stuff.” Woolie was a great leader making him be chosen to direct all the Disney films from Sword in the Stone to the Rescuers. “He had this persona like Twelve O’clock High Blood and guts,” remembers honoree John Pomeroy. “And that’s the way he did his movies. He was not always the most eloquent guy, the most sensitive guy, but damn it! He knew how to command!”

Wolfgang Reitherman was born on June 22, 1909 in Munich, Germany. Around 2 years old he moved to the United States where he lived in Kansas City, Missouri (later he found out he lived right around the corner from Roy O. Disney coincidentally) before moving to California in his later teens. Reitherman’s big passion growing up was flying and he dreamed of becoming a professional pilot. He became a very good one and flew all his life but he found out that in the Great Depression although he was briefly one after attending Pasadena College of art and Design. Searching for a new vocation Woolie turned to ambitions in becoming a water color painter and attended the Chouinard Institute of Art. “I didn’t really go to art school too well because I was spending most of the time sketching on my own and painting,” he remembered years later. “I was just fascinated with life and people, and once color grabs a hold of you, it becomes a thing!” While Reitherman’s watercolors show true talent and potential, he soon got recommended to apply to the Disney Studio, who was looking for artists, after graduating from Chouinard in 1933. He was reluctant because he thought drawing the same thing over and over again would get boring but after the first day he was hooked. “I just felt this was a twentieth century art form, probably the most unique of anything that had appeared on the art horizon for decades since perspective,” praised Woolie. “I was just fascinated because you could move those things. You can’t move a painting. And all of the sudden, on a white sheet of paper, you could make something move. The other thing that grabbed me was that it was about people and situations.” The last line is certainly true because his painting always showed people doing something and having intent as well as motion. Unlike most new animators, Reitherman never went through much of an apprentice system and was animating pretty soon after coming to Disney, starting with a few good scenes on the Silly Symphony Funny Little Bunnies. He also found Donald Graham’s action analysis classes very inspirational and stimulating. “We used to watch pictures in slow motion at night after work- sports, horse races in slow motion,” Wolfgang recalled in an interview. “And all you could do was talk about it, you never could grab hold of any fixed formula but finally things came to pass. You knew the weight had to be supported all the time because from birth to death gravity is working on you.”

Woolie Reitherman quickly improved artistically as an animator and soon was one of the most exciting and promising of the young animators at the studio. On Disney’s first feature, Snow White, he was given a very difficult, unappealing assignment: to animate the slave in the Magic Mirror. The Magic Mirror had to show virtually no emotion and didn’t have any more action, giving Reitherman not much to animate to and a very big challenge. “It was tough because it didn’t move,” said the animator. “It was just there all that time. I did that thing over and over again.” He even did the animation over again around five times and his solution to the problems of the character was that he drew one side of the face, folded the paper in half, and traced the first side onto the second side keeping the face symmetrical. So even at this early stage Woolie’s driven approach and brilliant problem solving was present in his art. The results worked great: the Magic Mirror has the most restraint actions and shows no emotion to what he is saying, making him believable and true to the story. Because of Reitherman’s accomplishments he was invited to give a few lectures to the younger animators such as this one: “I don’t want you to forget that creativeness, imagination, fantasy have to stay with you. You must stay pepped up on your work- you can’t get along a system alone. The first thing we come up against is sincerity and honesty by which I mean if a thing looks sincere on the screen, it looks as though it would really work, as though it would really work, as though it existed,…..as though gravity held it down. It looks plausible, feels logical….caricature or exaggeration in drawing is very important. The public never pays for a good drawing. It pays for an exaggerated effect. By caricature I don’t always mean funny drawing. If you are going to make a fellow loan over, make him lean over plenty. Go twice as far as you think you can in the drawing and you will always be about right. Make the character do everything he does in a decisive, definite way so that the audience will know what he’s doing. The drawing should be direct, definite, and simple. That means again you must have a clear idea of what you are after because it is hard to make a simple drawing. Harder than to make a jumpled-up drawing with all the details on it.” Around this time Woolie began to do a lot of animation on Goofy and after animating some brilliant personality animation with the character in Clock Cleaners (1937) he soon became the lead animator on the character for the studio. Among the best shorts he did on the character is Goofy and Wilbur(1939), which shows the animator’s great draftsmanship, knowledge of entertainment, and skill at doing expressive broad action that communicates an idea and feeling.

It was however the next film that made Wolfgang Reitherman become Woolie. It was Pinocchio and the scene was that of Monstro the Whale and his powerful chase of Pinocchio and Geppetto’s raft. “It was exciting because it was the largest thing we’d ever done on screen,” proudly proclaims Woolie on the scene. “And to get the weight and timing of al those things was a challenge.” The assignment was originally given to the great Bill Tytla, who animated all of Stromboli in the film, but Walt was unsatisfied and knew Reitherman would take the challenge to heart. This was perfect casting: he made Monstro have great power weight, and incredible force as he goes through the water. Add to that the genius timing, incredible sculpted draftsmanship of the whale, the amazing camera angles, the highest-caliber use of cuts, and most of all the incredible drama, suspense, and tension the audience feels when watching the scene. Woolie’s scene indeed revolutionized action scenes in the Disney films and most done since at least hold somewhat of a candle to it. On the same feature he did lots of juicy scenes with Jiminy Cricket including the scene where he’s pointing to the words with the cane on the letter from the Blue fairy. On the next film Reitherman would even take his art further and do an action scene that was equally if not more suspenseful, dramatic, and hair-raising. The film was Fantasia and he was given the difficult task of animating a battle between two dinosaurs: a T-rex and a stegosaurus. Walt made it clear what he wanted from Woolie: “Don’t give them cute animal personalities. They have small brains y’know; make them real.” Woolie went to many museums to study fossils of dinosaurs so he could get the anatomy and weight of the prehistoric creatures as accurate and powerful as possible. He then added to this his imagination of how a real dinosaur would move and the film techniques that would make the fight seem as dramatic and action-packed as possible. “I had to paste paper on it because I couldn’t draw it on a single piece of paper,” explains Reitherman. “And finally when the T. Rex grabbed stegosaurus by the neck…. I animated the whole big thing slowly going over and then the tail coming later. And then I just moved the camera along. It was very effective as I remember.” The scene certainly worked and the dinosaur fight is incredibly believable, cinematic, and true to the rules of action scenes in Hollywood. “Woolie’s stuff in the Rite of Spring has a monumental weigh to it, because Woolie in his own weight just kept after it,” praised Kimball on the scene. “it was a disarming request since there was little research possible on what a real dinosaur might have been like but Woolie was not bothered,” explained Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston. “He dipped into his imagination, combined with a few rare animal things he had seen and working closely with director Bill Roberts, came up with scenes of dinosaurs that seemed to be just the way these giants should be.”

In 1941 and 1942 Wolfgang Reitherman continued to show his great range and versatility as an animator. First on the Reluctant Dragon he animated the lion’s share of the How to Ride a Horse segment, which has come to be regarded as arguably his signature performance on Goofy. “How to Ride a Horse” (Goofy short) is a funny picture, one of the funniest shorts,” Ward Kimball told Steve Hulett. “As a shortism blockbuster, I know people who saw “How to Ride a Horse” in the theatre when it was released by itself ten or fifteen times. They would go just to see that and they would laugh and laugh ’til they cried.” This film was also a great collaboration between Woolie and a debut animator who would later become the Goofman of the studio: John Sibley. In comparison to Reitherman’s laborious reworking and sculpting of his work, Sibley was a natural and organically had a feel for how motions and emotions combine. Next the animator showed his warm side when serving as a directing animator on Timothy Mouse for Dumbo, focusing primarily on the early scenes with the character (Fred Moore, Milt Neil, and John Lounsbery did the character throughout the rest of the film.) Woolie’s animation of Timothy shows subtlety, richness of character, and sincerity, qualities that he has oftentimes been criticized for not having in his work. After that he animated Goofy again, this time in the El Gaucho sequence of Saludos Amigos. Reitherman did an amazing job at timing and caricaturing Goofy’s walks and movements to show his personality and make him believable. Also he animated the amazing dance sequence at the end, which is one of the greatest dance sequences in Disney history. In 1942 Woolie Reitherman left Disney to join the air force and fight in World War 2. Unlike many other artists who participated in the war effort, he didn’t just animate films for the government but actually was a war hero and flew in battle across the world. Immediately after the war ended Reitherman continued to be a pilot and did tons of long distance flights to Asia, where he met stewardess Jeannie who the bachelor married in 1946. After Jeannie became pregnant with their first child they decided to settle down a little bit and intended on moving to San Francisco. While going to say hello and goodbye to his friends at the Disney Studio with Jeannie’s approval Walt convinced Woolie to return to Disney for good in late April 1947 making them stay in Los Angeles.

“When I came back there was quite a lot of down feeling at the studio,” remembered Woolie Reitherman. His first assignment back was to resume animating Goofy in the package feature Fun and Fancy Free (he had begun to work on the Mickey and the Beanstalk segment when it was intended on being a feature.) Woolie’s triumphant comeback scene, however, was the Headless horsemen chase sequence in Ichabod and Mr. Toad, which played well with his broad action sensibilities. Next came Cinderella, which Reitherman actually helped convince Walt to make. “I tipped Walt dead center into making him decide to make Cinderella,” he recalled. “I just went into his office, which I rarely did, and I said ‘Gee that looks greats. We ought to do it.’ It might have been a little nudge to say ‘Hey let’s get going again and let’s do a feature.’” While Reitherman did some outstanding sequence with the King and the Duke which show great understanding of the character relationship and have great visual actions that clearly show the characters’ feelings his most famous scene in the final film is the intense climax where the mice Gus and Jaq have to carry the key up to Cinderella so she can get out of the room the Stepmother locked her in and prove that she was the girl the prince fell in love with at the ball. “There is no doubt that the key was too heavy for the two mice, that the pressure on them, mentally and physically, was tremendous, that at any minute Gus’s eyes could bulge out of their sockets or that Jaq’s face could turn purple,” wrote Thomas and Johnston. “The timing of these actions gave the frantic quality and the strength of the extreme drawings gave the impression of effort and exhaustion. The most important element in making the sequence so outstanding, however, was the fact that these little mice were doing all of this because they cared very much about the girl’s happiness. Usually this feeling of warmth can’t be structured in the story department and must depend entirely on the animator for its portrayal. It cannot be analyzed, or acted out, or represented in the same way as an expression or a passing thought since it is more of a sentiment that grows within the viewer from the special way the business has been animated. Actually it grows from the sensitivity of the animator who makes the drawings.” The mice-key sequence has the perfect combination of story, character, and technique; you really feel for the mice and their strong feelings for Cinderella. Woolie in particular did an incredible job with the cinematography in the scene and making you feel the weight the key has on the mice to make the emotion you have when watching the scene very effective.

Up next for Reitherman came Alice in Wonderland where he primarily animated the White Rabbit as well as some of the Dodo. Among his best work in the picture is the excellent character contrast between the cautious, worried White Rabbit and the arrogant, dominant Dodo seen in the sequence when Alice has grown huge and is inside the rabbit’s house. After Alice came Peter Pan, a film where Reitherman’s work has been well debated in terms of approach and character consistency. While both Frank Thomas and Woolie animated Captain Hook the character isn’t really the same character in the scenes the two men did. This is largely to blame on the indecisiveness of the story department and contradictory views about how the character should be handled. For example Ed Penner, one of the best storymen of the 1950s, wanted the character to be a very broadly-handled, comic villain while director Gerry Geromni wanted a more restrained, menacing villain. While Frank Thomas went with the more menacing approach Woolie went for the more comic approach, much to the other animator’s resentment. “The broadest sort of comedy intrudes suddenly in Peter Pan even when the threat of dearth is supposed to be taken seriously,” wrote Michael Barrier in his book Hollywood Cartoons. While I don’t necessarily agree with Reitherman’s decision in regards to character his animation of Hook is certainly very entertaining and cartoony. “It was so much fun because I got that sequence with very little to go on,” recalled Woolie on his animation in the scene where Hook is in the cave. There is however one scene that he animated that really shows his subtle, complex side: the scene of Hook climbing up the mask towards the end. The anger, resentment, and animosity he feels towards Peter Pan is so prevalent in the character’s expressions in that scene as well as when he flings the sword. “Woolie did fantastic Captain Hook scenes where he is climbing the mast, very distraught,” Andreas Deja told John Canemaker. ‘Camera looking down. Great acting scene. Woolie also did a lot of action but that scene showed me he was capable of great insight into the character.” On the next feature, however, Wolfgang got some of his most dramatic, intense action sequences in his career that even go up there with those in Pinocchio and Fantasia. The film was Lady and the Tramp and he got two very juicy action sequences: the one where Tramp saves Lady from the stray dogs when she’s in a muzzle and the one where Tramp fights the rats in the baby’s room. The former is particularly intense and the pacing of that scene is perfect. You feel the threat the other dogs have towards Lady and even are convinced they’re going to win but then heroic Tramp comes to the rescue. “What I wanted to do was simple have a chase, corner and then pow!” said the animator. “And then a moment of pause. And don’t fool around with it. And then drive in and then go like everything! Then it had the great thing in it which was biting the rear hack of a dog and they all fled.” “Generally you like to feel the bad guy is going to win, and the good guy is going to come back,” stated Reitherman. “And eventually the ebb and flow of that battle changes that the good guy wins. But I think it is very effective in action sequences if you can stop for a minute because again it is just too much to absorb. When it starts again, it gives the audience a little jolt.”

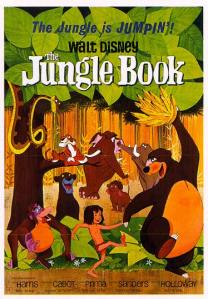

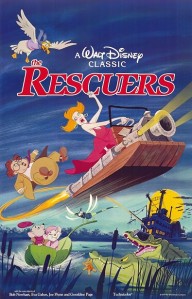

Lady actually proved to be Reitherman’s last animation in the Disney films and he soon moved into directing, starting out with the short What’s the Truth About Mother Goose (1957.) Even before then he would oftentimes supervise other animators in the B-Wing such as Eric Cleworth and John Lounsbery and have them animate shots in his scenes. Up until the early sixties Woolie directed a lot of the occasional shorts still done by the studio including Goliath 2, the first ever use of the Xerox system. However the scene that really proved to be his breakthrough as a director was when he directed the sequence in Sleeping Beauty where Prince Phillip fights Maleficent in the form of a dragon. “We took the approach that we’re going to kill that prince,” Woolie once proudly said. On One Hundred and One Dalmatians he directed the Twilight Bark sequence as well as the Cruella de Vill crash scene. However the need for a major director in feature animation was becoming desperate. The beloved and heavily admired Wilfred Jackson had suffered a heart attack in late 1953 while directing Sleeping Beauty and never was the same after that. When he returned in 1954 he begun to work in TV for 5 years but the stress of directing a TV show really got to him making him take a leave of absence in 1959 and fully retire in 1961. The notorious, hostile Gerry Geromni had developed such a bad reputation with the animators that they began to refuse to work for him and he was let go in 1959. The respected but more passive Ham Luske was moving more into television and becoming less focused on feature animation. This left the sport open for someone knew and Woolie it was to take it. “They picked out a guy who wouldn’t give them much trouble,” once said Ward Kimball. Starting with Sword in the Stone and ending with the Rescuers Reitherman directed all the Disney films (Jungle Book, Aristocats and Robin Hood in between.) Among his virtues as a director were that he was open to new ideas, was able to make a movie on time and on budget(although with a very small staff the films took a long time to make and the budget does oftentimes show in the production quality), and that his films do entertain even though they don’t do much to affect you in the heart and are pretty uninspired. On the flip side he was pretty uncreative, used the same voice talents over and over again, his storytelling is well below adequate and overly simple, the characters are repetitive, he used a lot of recycled footage(even used the animation from the Silly Song sequence in Snow White for a dance sequence in Robin Hood), and most of all nothing innovative or original was done in his films. “He’d never go back and say ‘Well let’s see what did you do here?’ Like Ham Luske would have done, try to understand the whole thing,” said Frank Thomas. “If Woolie didn’t understand it he’d tip the boat over.” Among Reitherman’s harshest critics were great animators Ward Kimball and Milt Kahl (he even was a factor in the later man’s decision to quit animation in 1976.) “I can’t cope with this man, absolutely can’t cope with him,” said an angry Milt Kahl. I detest the use of—it just breaks my heart to see animation from Snow White used in The Rescuers. It kills me, and it just embarrasses me to tears. I went back to Florida with Woolie for a party for the wire services and the press for Robin Hood. And I met a guy who about twenty years ago I met at a friend’s house; he was with Paramount at the time, a publicity man. His name was Emory Wister; he worked for the Charlotte Register [probably the Observer]. He is a Disney buff, an animation buff. And these guys always scare me, because they know more about the pictures than I do. And he recognized this goddamned animation, where Maid Marian is dancing around with little creatures; he recognized it from Snow White. This is our Woolie, and it drives me crazy.” In 1977 Woolie stepped down from the director’s set but continued to serve as the producer of Fox and the Hound until his retirement in 1981. Sadly he died from a car accident in 1985.

Like I said above Wolfgang Reitherman was a man for broad action whether it was intense, suspenseful action or broad comedy. He was very intense artistically and always pounded hard to get the most entertainment and effect out of a sequence. Woolie wasn’t very good at subtleties and warmth but he definitely understood the characters he was animating and the aspects of great filmmaking. He thought more in terms of cinematography than the other animators and his scenes show great camera angles and cuts. As a draftsman Reitherman was very bold and strong, which helped give his work the great vitality it has. As in how Woolie got this all in his animation it came from the hard work and constant reworking he did on his drawings. “Woolie started with scribbling the power of the drawing. You couldn’t see a character in there,” remembers Don Bluth. “Then he’d put a piece of paper over that and finally get a character to represent the powerful scribbles that were just pencil marks on a page. So it took him two or three generations to find that actual drawing.” In terms of how the animator worked listen to what he had to say in this quote: “I start by going over story points because the idea you are trying to put over must be very clear in you mind. I try to use my creative imagination to build what I am trying to put over, rather than go off on a tangent by myself and come back with a version that the director never dreamed of. Next I review the layouts and staging. I see my characters have plenty of room to work in. I plan my action as though the paper actually were a stage. I draw key poses and consider almost every verb in an action: the character walks or sits down or gets up. I try to make a story of each one, visualizing how I would work in and out of those poses. In planning a scene using key poses I feel you must caricature each pose, go further with it each time and also try to put as much of the mood and the feeling of the character itself into that pose as you possibly can. I then act out the business with my assistant. If it’s not as clear and direct as possible I start over. The scene becomes more flavorful as it’s boiled down. Then I begin to get satisfied. When the work begins to get simpler, it’s good. When it’s complicated it’s not. Finally I animate straight ahead using key poses as goal posts to get a flow and feeling in the animation.

Wolfgang Reitherman is one of the most influential artists in Disney history. His action sequences were revolutionary and they literally changed how action sequences were done at Disney forever. Name any action sequence in a Disney movie and it gets to the point it’s pretty cliché to say it holds a gigantic candle to Reitherman’s work. Woolie also really influenced how broad action was done in Disney films particularly through his work with the character of Goofy. As a director I would have to say he’s by no means the best director in Disney history but he owes a lot of credit for keeping the department and the studio afloat. Reitherman will always be remembered as a brilliant animator whose unique sensibilities helped change Disney animation forever.

In terms of inspiration I feel that Woolie Reitherman has had a big impact on me not only artistically but also in terms of filmmaking. The staging and cinematography he put in his scenes really speak to me and I’m a nut for the composition seen in his shots. In art and animation his unique approach and sensibilities helped teach me there are 1,000 ways to animate a scene and that there isn’t a right or wrong approach to them. Some people do well with subtle sentimental stuff but others work well with broad, over the top action. The point is that all can be great character animation and can work well in a film. Thank you Wolfgang Reitherman for your contributions to the art of Disney Animation and for the influence and hero you’ve been to me as well as so many other people!

September 27, 2011 at 4:34 am

Woolie did some wonderful subtle animation in Lady and the Tramp. When Lady and Tramp wake up the morning after the Bella Notte sequence–watching the sun rise. One of the yes scenes in the picture–and virtually all Woolie.

February 9, 2012 at 2:18 am

I lived next to the Reithermans in Burbank, and babysat Richie, Bobbie and Brucie. I even remember their dog, a boxer, Count. That was 55 years ago. Wonderful memories.

June 18, 2012 at 8:41 pm

I lived up the street from the Reithermans…went to school with his older son Dick Reitherman. Always remembered Woolie is a very warm and friendly guy..during jr. high, Woolie was always there to pick us up after school. We all new he worked for Walt Disney, however, never new how great an animator and director he was until many years later. Remember how sad I was about reading of his death in 1983. RIP Woolie and thanks for all the memories.

April 2, 2012 at 4:37 am

No one could do a better chase sequence than Wolfgang Reitherman–NOBODY! I especially loved the Monstro the Whale chase sequence & most definitely the Headless Horseman chase sequence! Actually, Lady and the Tramp was his 2nd to last animated work: Sleeping Beauty was his ACTUAL last film he animated & also the first he directed. How do I know? Well, I researched him while researching the Nine Old Men & I learned that he created the dragon from Sleeping Beauty. Also, if you look at it, it has similar eyes & mouth as the Rat in Lady and the Tramp & a similar snout as the Crocodile in Peter Pan. Oh, & you forgot that Woolie didn’t just do Captain Hook in Peter Pan; he also did the Crocodile. I’m not trying to make you feel like an idiot; I’m just saying from what I’ve read about him. Oh, & one more thing: in Ichabod & Mr. Toad, he also animated two juicy scenes in the Mr. Toad segment: half of Toad’s escape from prison & the battle of Toad Hall when Toad, Rat, Mole & MacBadger retrieve the deed from the weasels & Mr. Winky, not to mention another part of a scene in the Ichabod segment, at Baron von Tassel’s Halloween party when Brom Bones fell through the cellar door & when Ichabod danced very fast while balancing on a pumpkin. Thanks for all this stuff on the animators; great picks for the top 50!

April 6, 2012 at 9:43 pm

Actually Woolie only directed the dragon sequence in Sleeping Beauty, according to the draft he did no animation on the film. Although a lot of the staging and pacing has Woolie written all over it the man who really animated most of that fight was Eric Cleworth. You are right that Woolie did animate some of the crocodile but a lot of the great stuff was done by a forgotten animator named Jerry Hathcock.

April 11, 2012 at 7:53 pm

Really? Because the dragon was said to have been animated by Wolfgang Reitherman. And Eric Cleworth was under Woolie’s unit when he first joined the–say, what did Eric Cleworth do in Peter Pan, then?

April 25, 2012 at 2:24 am

Where can I find the draft for this movie–in fact, for ALL Disney films? ‘Cause I’m sure there must be some mistake….

June 9, 2012 at 3:56 am

Here’s the Sleeping Beuaty Draft-http://afilmla.blogspot.com/search/label/SleepingBeauty. On the site A Film LA there are drafts posted for about 2/3s of the classics with Walt. Eric did animate some of Captain Hook in Peter Pan.

July 17, 2012 at 10:44 pm

Thanks!

August 14, 2012 at 1:05 am

I personally love the contrast in character Woolie’s comedic approach brought to Captain Hook. It made the character very rich and unique. On one hand he was very stately and sophisticated and on the other hand clumsy and comically incompetent, which contrasts perfect with his stately demeanor.

It’s one of the reasons Captain hook is one of my favorite Disney Villains. I can understand why the animators would object but in the end it worked perfectly if you ask me.

December 29, 2013 at 10:16 am

Wollie was my uncle. I grew up in Fresno, and recall seeing him only a few times when he and my Aunt Janie (that was what she was called at the dinner table) came north for family functions. He was, as I recall from a very young child’s perspective, a very serious person, yet had a smile that made me feel very much at ease. He was Uncle Wollie to us all.

January 9, 2014 at 3:31 pm

I was watching The Fox and The Hound with my children and I wondered to myself where did all of the great movie makers go? So I typed Reitherman into Google and here I am I reading about this fascinating man whose work is by far unsurpassed.